Masked Diffusion Language Modeling for Conditional Small Molecule Generation

Small Molecule Generation

Most pharmaceuticals are small molecules. Conditional generation of small molecules is extremely valuable as the success of a small molecule therapeutic is dependent on a number of factors such as binding strength, specificity, ADMET properties, etc. As a simple experiment to evaluate the capabilities of MDLM, we explore the toy case of text-guided molecular generation.

Why Diffusion?

Discrete molecular representations are not inherently sequential in the same form as text or bytes representing a program. For small molecules, the order of tokens matters far less than the overall connectivity and three-dimensional arrangement of atoms, making non-sequential generation much more appealing. Diffusion has also been shown to be better equipped for conditional or guided generation, which can be very beneficial for molecular generation since we often want to optimize select properties in molecular libraries while still producing a diverse set of molecules.

Why Discrete Diffusion?

Since most small molecule representations are inherently discrete (either graph based or string representations called SMILES), it is intuitive to work in the discrete space to preserve molecular validity. We started with SMILES for simplicity and as a “first pass” validation of MDLM.

Side note: The argument for discrete representations of small molecules is weakening as continuous predictive tasks gain more research interest in molecular generation (ie. denoising 3D atomic coordinates and then running external cheminformatics software to determine bonds/atom types). However, since CHEBI-M is limited in scope, it made more sense to reduce complexity of the generative task and work in the discrete space for this project.

Why MDLM?

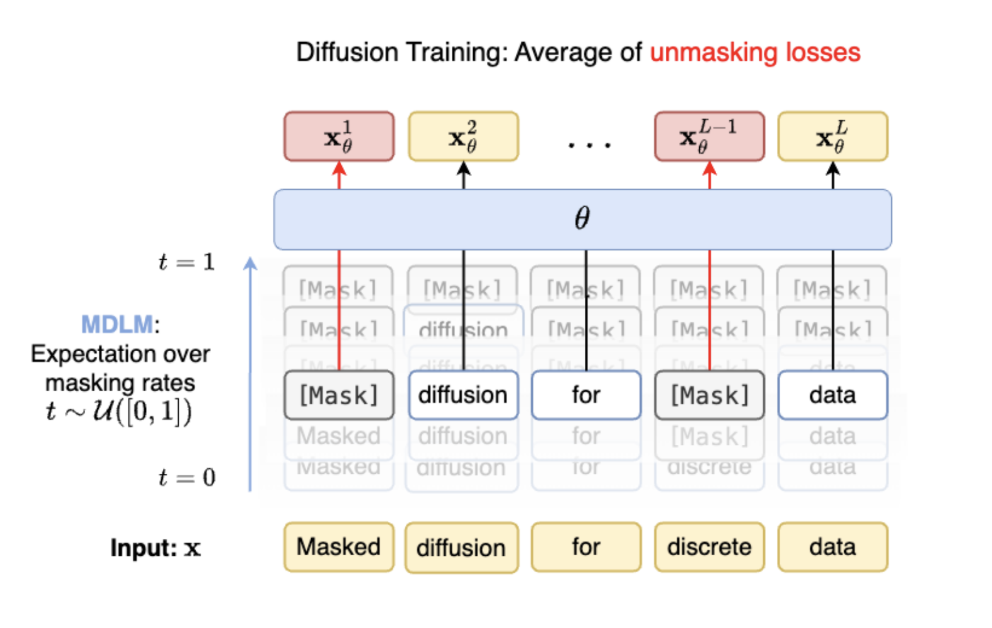

Rather than projecting discrete data to the continuous space and denoising, MDLM is a form of diffusion defined entirely in the discrete space where “noise” can be thought of as iterated masking of tokens and “denoising” can be thought of as iterated unmasking of tokens following the defined noise schedule.

\[q\left(\mathbf{z}_s \mid \mathbf{z}_t, \mathbf{x}\right)= \begin{cases}\operatorname{Cat}\left(\mathbf{z}_s ; \mathbf{z}_t\right) & \mathbf{z}_t \neq \mathbf{m} \\ \operatorname{Cat}\left(\mathbf{z}_s ; \frac{\left(1-\alpha_s\right) \mathbf{m}+\left(\alpha_s-\alpha_t\right) \mathbf{x}}{1-\alpha_t}\right) & \mathbf{z}_t=\mathbf{m}\end{cases}\]

MDLM is also absorbing state, meaning that once tokens that are masked during the noising phase, they remain in the masked state for the entire noising phase and tokens that are unmasked during denoising remain so for the remainder of denoising. By taking T in the limit, we get a simplified training objective that is easily computable given logits and alpha (which is interestingly a weighted average of traditional masked language modeling losses per token!).

\[\mathcal{L}_{\mathrm{NELBO}}^{\infty}=\mathbb{E}_q \int_{t=0}^{t=1} \frac{\alpha_t^{\prime}}{1-\alpha_t} \sum_{\ell} \log \left\langle\mathbf{x}_\theta^{\ell}\left(\mathbf{z}_t^{1: L}, t\right), \mathbf{x}^{\ell}\right\rangle \mathrm{d} t\]

The full paper and a great in depth explanation of MDLM can be found here, but given the impressive test perplexity compared to traditional discrete diffusion and AR networks, I wanted to see if this method would work well for the more domain specific task of molecular generation.

Modifications

Atom group SMILES tokenizer: Custom tokenizer for SMILES that treats atomic groups explicitly as separate tokens, parentheses and ring numbers are individual tokens. Other work has shown that this type of explicit tokenization tends to outperform standard BPE for SMILES generation.

DiT text guidance: Added cross attention to DiT backbone for text guidance across concatenated BERT embeddings. This concatenation can be done with any projection, but given higher quality of pretrained BERT embeddings (compared to scalar projections which most property optimization would require), text guidance was a reasonable first test case.

Upweighted EOS token for length prediction: There are a few ways to handle length prediction (for autoregressive models, you would not need to worry about this, EOS token with enough examples falls out). However, with a more limited dataset, there were some issues with length tallying, as the model tendency is to produce longer outputs. To overcome this, upweighted EOS prediction loss in the loss function to effectively serve as the length prediction function (could also simply upweight the padding token but this was less effective).

Validity tuning: SMILES follow a hyperspecific grammar required in order to produce what is considered a valid molecule. Model did not show many valid molecules despite a relatively high BLEU score. Added differentiable loss terms for ring, valence, and parentheses. Used logits to maintain smooth loss function and tested a few different values for lambda. Simple loss function is below. Tested for different lambda coefficients as well, reported best performing lambda value (0.1).

Negative Infinity Logit Bug: Once a token is denoised, the logits for the masked state are set to negative infinity. However, the mask was not updated to ignore the negative infinity logits for the masked tokens in the loss calculation, resulting in unstable training and lots of NaNs.

Results and Conclusions

Although MDLM achieved higher BLEU scores than the AR transformer, it significantly underperformed the continuous diffusion SMILES generator (TGM-DLM) in both BLEU score and validity, indicating that improvements in discrete diffusion are required before replacing continuous diffusion methods.

| Model | BLEU Score | Validity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| AR Transformer | 0.422 | 0.906 |

| TGM-DLM (cont. diffusion) | 0.828 | 0.789 |

| SMILES-MDLM | 0.678 | 0.000 |

| SMILES-MDLM (with validity tuning) | 0.664 | 0.167 |

Structured output remains a challenge for diffusion models

Diffusion-based models struggle with structured output tasks such as molecular generation. Despite achieving moderate BLEU scores, the validity of the MDLM generated molecules remains severely lesser than other methods. For instance, the base AR Transformer exhibited the highest validity (90.6%), far outperforming SMILES-MDLM even after validity tuning. The ineffectiveness of the validity tuning also indicates that MDLM models are more difficult to train for validity. This highlights that AR models may inherently be better suited for tasks requiring strict adherence to structured grammars, such as generating valid SMILES strings, due to their sequential generation process that may enforce syntax more robustly.

Small vocabularies limit MDLM Performance

SMILES representations inherently have a small vocabulary size, as most organic compounds are made of a small set of atoms and are typically no more than 100 atoms. In the CHEBI-20 dataset, 91% of SMILES were below 156 characters, resulting in a small vocabulary of 282 tokens across the 32,000 examples. While BLEU scores indicate reasonable linguistic similarity, the constrained vocabulary appears to amplify errors in generating valid molecules. This issue is less pronounced in language-based tasks, where the large vocabulary size better aligns with MDLM’s strengths. BPE could have mitigated these issues, but the short sequence lengths in SMILES further reduced its potential impact. However, it should be noted that MDLM may perform better in other domains with larger vocabularies or with other discrete representations such as graphs.